ThousandEyes has been actively monitoring Internet conditions in Russia over the last several weeks to understand the health of backbone connectivity keeping Russia connected to the world, as well as the availability of sites for users both in and out of Russia, when traversing between the Russian Internet and global Internet. This analysis is ongoing, and we will update our findings as conditions change.

Summary of Findings

[As of March 10, 2022]

- Backbone Internet connectivity to and from Russia does not appear to be limited or constrained despite recent reports of major global transit providers “disconnecting” from Russia. Russia’s connection to the global Internet continues, enabling traffic to flow into and out of the country—at least at an infrastructure level.

- Access to certain Russian sites for government, energy and banking entities has been impacted by traffic blocking implemented by ISPs and site owners based on the source and/or destination of the traffic. In some cases, this filtering was precipitated by prolonged periods of heavy traffic loss indicative of congestion commonly seen during DDoS attacks.

- As observed with Ukrainian websites, cloud-based security solutions, when used, have been effective at enabling services to remain available, while shielding them from denial of service and other attacks.

For the latest threat intelligence from Cisco Talos on the developing situation, see here.

State of Backbone Connectivity

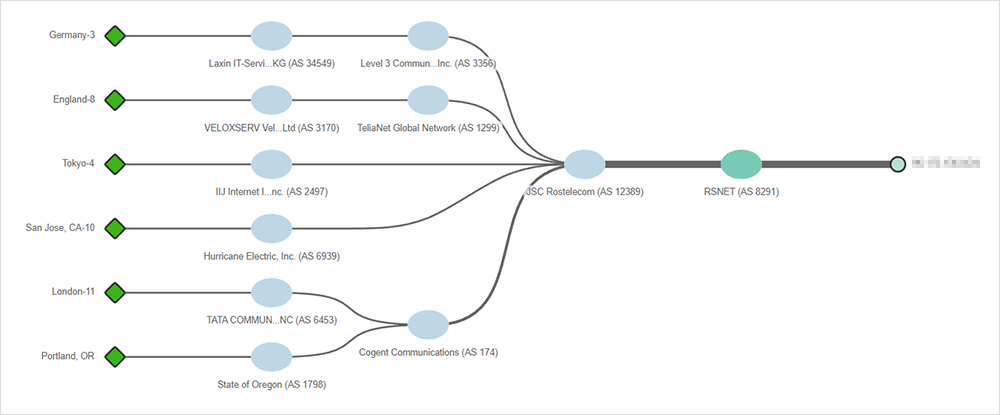

Transit providers are the service providers of service providers, they connect not individual users but ISPs to one another to effectively serve as the backbone of the Internet. Much has been speculated recently about their potential role in disconnecting Russia from the rest of the global Internet. However, Russia’s connection to the rest of the world via these vital networks remains intact, with major Russian ISPs, such as JSC Rostelecom, continuing to peer with global transit providers outside of Russia, just as they did long before recent events. As a result, the Russian people continue to have access to the global Internet—at least at an infrastructure level.

Despite the notion that some U.S.-based transit providers would “disconnect” Russia from the Internet—no single transit provider severing ties with Russian ISPs would achieve such an aim. That said, many transit providers, both U.S.-based and non U.S.-based, continue to connect their global customers to one another—that may include providing transit to and from Russian users via major Russian ISPs located at exchange points not on Russian soil.

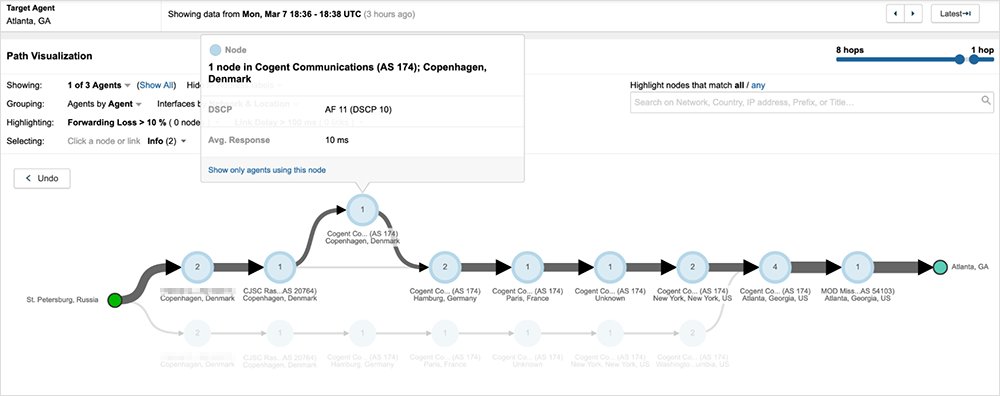

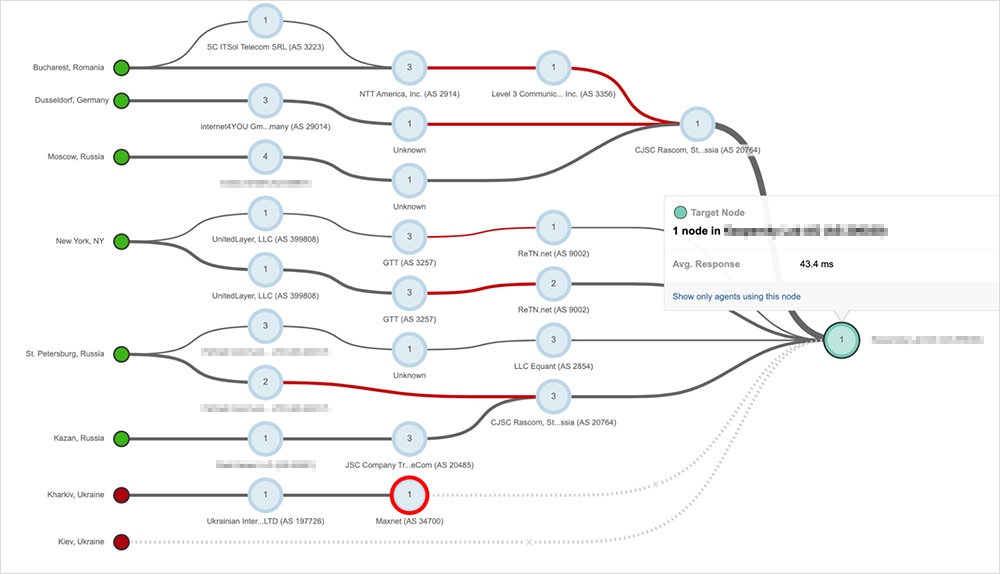

For example, figures 2-4 show Cogent serving as a transit provider between JSC Rostelecom (AS 12389) and CJSC Rascom (AS 20764) and the rest of the Internet.

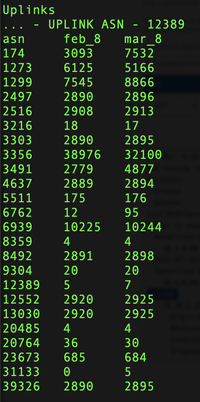

To illustrate the current state of connectivity between transit providers and Russian ISPs, we compared the announced prefixes and uplink providers for JSC Rostelecom (AS 12389), Russia’s largest ISP, as they appeared in global BGP routing tables (based on 32 BGP monitors distributed across all regions) on February 8, 2022, and March 8, 2022. As seen in figure 5, within that period, the number of times Cogent appeared as the UPLINK AS to JSC Rostelecom increased by over 140%.

Level 3 (Lumen) is another transit provider that currently exchanges traffic with major Russian ISPs at locations outside the country—just as they have historically. Figure 5 (asn 3356, row 8) also shows Level 3’s uplink frequency for JSC Rostelecom, which though they slightly decreased over the past four weeks, shows their baseline in February at nearly 10x over Cogent, continuing to be the most frequently occurring uplink provider for this Russian ISP.

In addition to Cogent and Level 3, many other globally-operating transit providers, such as TeliaNet (AS 1299), Telstra (AS 1221) (and more), also continue to peer with major Russian service providers at locations external to Russia, providing transit for traffic originating from or destined to the country. It’s important to note, however, that just because network connectivity persists between Russia and the rest of the world, as it does with China, that doesn't mean that the Internet experienced by Russian users mirrors that of the rest of the world—or that users outside of Russia have unfiltered access to websites served from inside of Russia. Ultimately, other methods of access control can be implemented to block unwanted users or unwanted applications, in effect, creating a virtual Internet partition.

Internal and External Access to Key Russian Sites

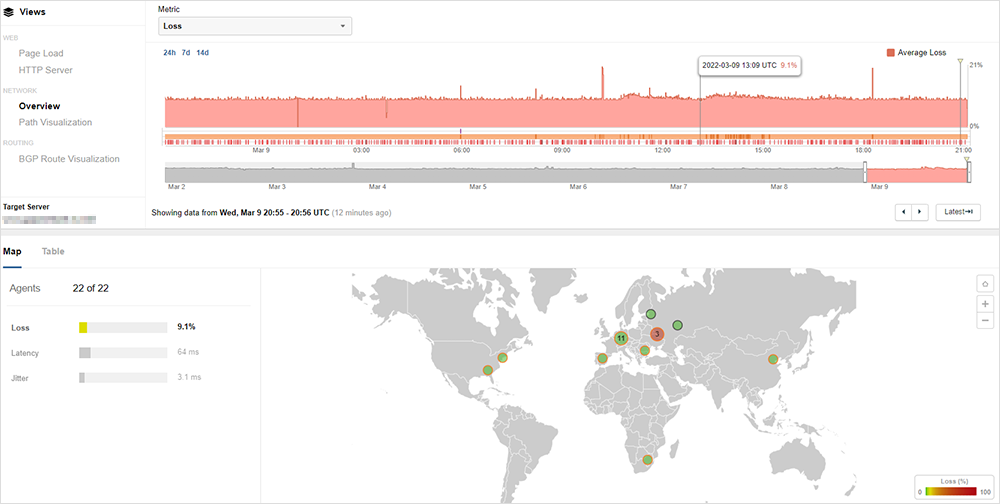

Similar to ThousandEyes findings on site availability of Ukrainian government and banking sites, Russian sites have also shown evidence of distressed network conditions indicative of DDoS attacks, as well as behavior consistent with route filtering, firewalling of traffic and, in some cases, cloud-based DDoS mitigation. The latter blocking mechanisms have predominantly impacted users external to Russia.

Looking at the availability of Russian sites belonging to government entities and energy, mining, and banking companies, we see that most have experienced substantially reduced availability subsequent to the invasion of Ukraine on February 23, 2022. For example, the website belonging to a government entity exhibited what appears to be normal behavior (nominal packet loss and normal server availability) from global locations prior to February 25, 2022. Then, starting around 23:30 UTC on February 25th, ThousandEyes observed a significant increase in packet loss connecting to the site, which impacted web server reachability.

Between February 25th and March 1st, network conditions appeared erratic, with varying levels of high packet loss, followed by periods of 100% packet loss for either all users or only traffic originating outside of Russia—possibly due to source IP or network based filtering. Beginning in March, the site has largely been available only to some users in Russia (while some traffic originating in Russia is also blocked).Looking at the network path, we see that all packet loss is occurring at the service provider for the government entity website. This could indicate that packets are being dropped due to route-based filters that are designed to blackhole traffic (see figure 7).

Traffic blackholing implemented at the ISP level, as appears to be seen with the government entity website, is a technique often used to combat DDoS attacks, even though it can be imprecise and cause significant collateral damage in preventing non-attack traffic to reach a site. Despite these downsides, ThousandEyes has observed blocking patterns across many sites in Russia as well as Ukraine over the last couple of weeks that are consistent with traffic blackholing implemented via ISPs.

The website belonging to a major Russian energy company appears to be using similar protective techniques. ThousandEyes sees HTTP results failing due to a timeout and observes 100% packet loss between an upstream provider and the energy company’s service provider, indicating that the packets are likely being dropped at the IP filter level at the ingress interface of the energy company’s service provider. Traffic from global locations is effectively getting dropped, but so too is traffic from some Russian users.

Other sites, such as one belonging to a large Russian bank, are similarly unavailable for users connecting from global locations; however, unlike the energy company site, it has remained largely available to users within Russia.

A closer look at this site reveals that the inability of global users to connect is not due to packet loss at the ISP level. As seen in figure 10, average packet loss, while present, is relatively low and entirely contained to loss sustained by Ukraine traffic. It is not the root cause of broader connectivity failures.

For most locations, BGP is properly routing traffic, and no issues are seen along the network paths to the banking site (as seen in figure 11).

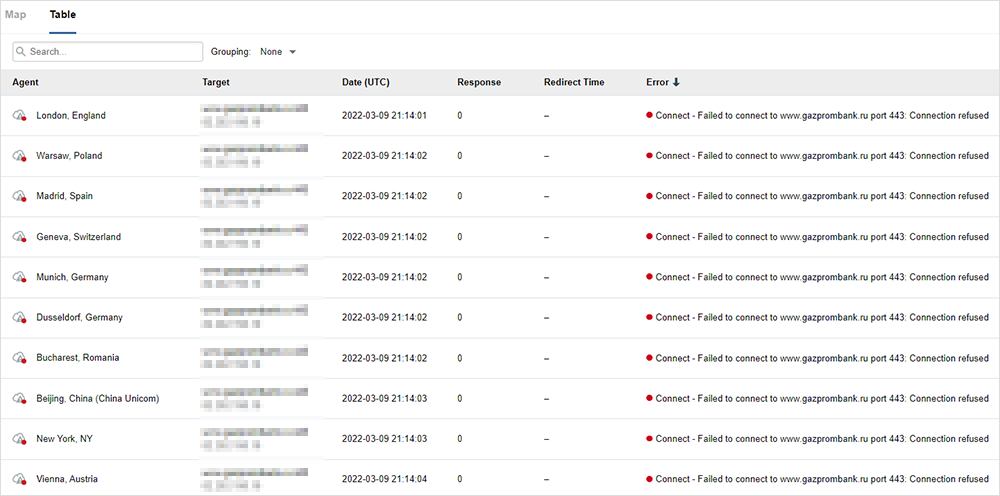

Drilling down to see the cause of the failure from an HTTP perspective, we see that for the failing sessions, the website cannot be accessed over TCP port 443, and the connection is refused at the TCP layer.

This indicates something stopping the traffic at Layer 4, such as either a Web Application Firewall (WAF) or a traditional network firewall. Implementing WAF or firewall policies to filter traffic when the source IP is within a geolocation IP range is a fairly trivial thing to implement to protect individual websites.

Of note, all three Russia locations are able to access this website and receive HTTP 200 OK responses, indicating that the filtering is likely done by IP address geolocation to filter all traffic either from specific countries or possibly from anywhere outside of Russia.

Another security approach observed was that of the Russian-language website of a mining company with primary operations in Russia. As seen below, all locations are failing to access this URL, including all Russian locations.

Similar to the banking site, the issue is not due to packet loss or something at the IP layer. Rather, we see that the website or its proxy is sending an HTTP 403 Forbidden response (see figure 14).

In this case, we see that the mining company is using a U.S.-based CDN for DDoS mitigation and other security protections. A 403 response means that the web request reached the web server, but that the web server (or proxy) responded with a 403 Forbidden response indicating a security rule set was triggered, denying the session, but also providing a browser-based mechanism for legitimate users to validate themselves as human in order to gain access the site.

We are continuing to monitor the situation for new developments.

Takeaways and Recommendations

- Despite reports of Russia’s possible disconnection from the global Internet, connectivity continues as it has historically, with global transit providers exchanging traffic with major Russian ISPs at locations outside of Russia.

- In observing recent Internet conditions in Russia (and Ukraine) involving denial of service and other malicious attacks, some security approaches have been seen to be more effective than others:

- Traffic blocking implemented through ISPs may be effective for protecting sites under D/DoS attacks; however, its significant collateral damage to legitimate users makes it less than optimal when under sustained attack from a wide distribution of sources.

- While locally implemented security protections, such as firewalls and intrusion detection/prevention systems, may offer more targeted options to deny access to unwanted connections, if a site is dealing with a sustained volumetric attack, a more distributed architecture and sophisticated blocking approach, such as that offered by cloud-based security providers, may be more effective in both protecting a site and allowing access to legitimate users.