While service access across Ukraine continues to be volatile, in the interest of shining a light on how recent days have unfolded from an Internet perspective, this post describes conditions surrounding the availability of major banking and government sites and how they are faring thus far. We will post additional updates on regional conditions as they evolve.

Summary of Findings

[As of March 2, 2022, at 2pm PT]

Over the past two weeks, ThousandEyes has observed the following:

- Significant levels of Internet traffic disruption and reduced availability of key Ukrainian banking, defense and other government websites: The patterns of disruption are consistent with network behavior we have observed during other distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, as well as indicative of potential countermeasures that may have been taken by service operators to mitigate impacts to their service. Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) is a form of cyber-attack where an online property (website or service) is intentionally flooded with high volume of unsolicited traffic originating from different parts of the world, with the intent of overwhelming the infrastructure and services and preventing legitimate traffic from getting through.

- DDoS mitigation, when employed via cloud services providers, has largely been effective: The websites and services that have deployed large-scale cloud-based security providers (such as Imperva, Cloudflare, etc.), either for a period of time or switching recently during the last week, have been able to more effectively maintain uptime and access. These DDoS mitigation providers typically redirect traffic through their own infrastructure, which can manage higher traffic volumes as well as use techniques to scrub malicious traffic and send legitimate traffic to the actual destinations. We are seeing some defensive techniques of selective blocking of traffic originating from Russia and, in some instances, China. A lot of the websites and services that have not upgraded to scalable delivery architectures or more robust security mechanisms continue to experience significant disruptions.

- No evidence of large-scale DNS or BGP attacks as speculated: This does not mean that they were not attempted. If there were attempts of DNS or BGP hijacks, they were either limited or largely ineffective in causing widespread impact. DNS is the global naming system that translates domain names (such as twitter.com) to an IP address (such as 104.244.42.65) where the service is hosted. Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) is the communication protocol between Internet routers across organizations and countries, ensuring traffic gets from the source to the correct destination IP via parts of the Internet. A DNS hijack is a technique used to direct users to illegitimate destinations by providing incorrect address information. BGP hijacks may be accidental or intentional and result in redirecting traffic away from the intended route or legitimate destination. Both DNS and BGP are fundamental to the operation of the Internet.

Key Takeaways

[As of March 2, 2022, at 2pm PT]

Large-scale cloud-based security services have successfully enabled banking and key government defense sites to remain available despite significant volatility in the region. Organizations weighing the impact of this volatility on their digital infrastructure should consider the following:

- Scalable service delivery architectures with redundancy across all critical dependencies (DNS, ISPs, hosting, etc.) and frontended by distributed infrastructure with well-provisioned security capabilities are best suited to maintain resilience under adverse conditions.

- Cloud security service providers are fielding significant volumes of traffic at this time. Customers of these providers who are not experiencing an attack could potentially see collateral performance impact to their services and should have a plan B in place for these events.

- DNS and BGP, while not seen as attack vectors, remain points of potential vulnerability and should be closely monitored for impact to sites inside Ukraine and even beyond.

For the latest threat intelligence from Cisco Talos on the developing situation, see here.

In-depth Analyses/POVs

[As of March 2, 2022, at 2pm PT]

Ukraine Government Websites

Connectivity to government websites has been highly volatile, ranging from low to high levels of loss indicative of changing states of congestion within local networks to rapid, 100% drops in traffic from specific sources, likely due to the application of traffic blackhole filters implemented by site owners via their service providers.

While DDoS-related congestion and countermeasures (such as traffic blackholing) are likely contributors to some of the traffic patterns observed, non-malicious traffic growth due to increased international interest, as well as security mechanisms (such as DDoS traffic scrubbing and network intrusion detection and prevention systems) may also have played a part in increased traffic loss and overall reduced availability of some sites.

Regardless of specific cause at any point in time, the net impact has been significant variation in Internet connectivity and application availability (even for the same service), with accessibility of key government sites ranging from 0–100% — in some cases, shifting between those extremes within minutes depending on traffic source.

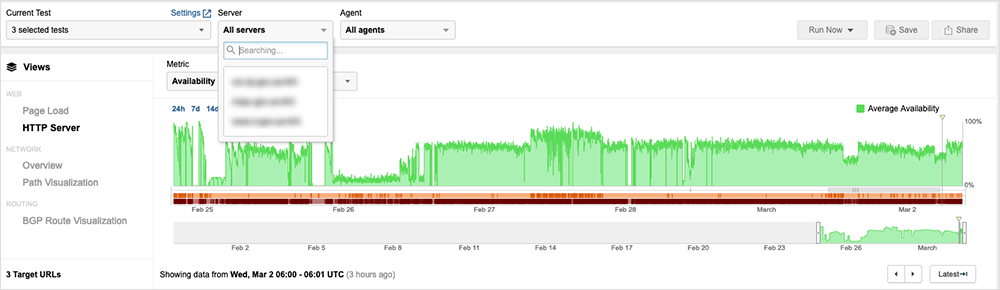

Two service delivery approaches appear to directly correlate with the different levels of availability, with sites fronted by highly scalable cloud services, such as globally distributed CDN and web security services, faring far better than sites that continue to be served solely from local infrastructure. For example, many government sites are hosted in single locations, share common infrastructure with other government sites and connect to users through one or two local Internet service providers. These sites continue to experience significant levels of disruption as shown in Figure 1 where multiple sites belonging to the Ukrainian government are in the same hosting environment and share the same IP address and Figure 2 showing the sustained network degradation.

Clustering these sites on common infrastructure could have led some sites to experience degraded conditions due to malicious traffic directed at a co-hosted site under attack in addition to the infrastructure and network along the path. Moreover, if more than one site was under attack, separately targeted streams of traffic could have an amplified effect as they converged onto a smaller number of ISPs and, ultimately, a single site.

In contrast, a subset of government sites that were leveraging or started leveraging cloud services for protection and distributed site delivery have largely remained available. In some cases, we’ve observed the migration of key defense and intelligence sites to globally distributed CDN providers, presumably precipitated by recent events.

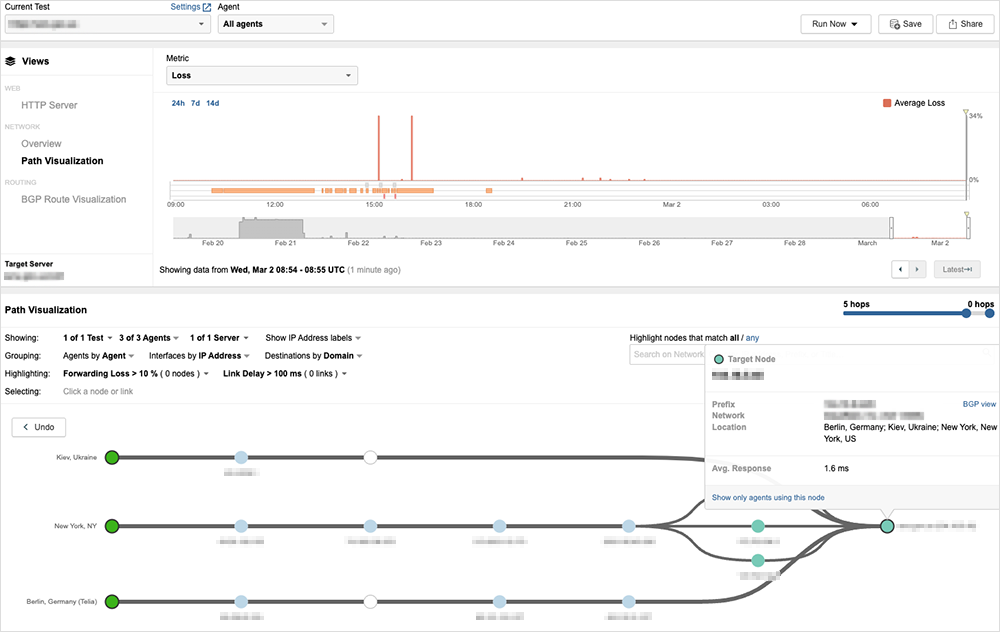

Figure 3 shows the sustained periods of network degradation for one Ukrainian Government Agency website on it’s original hosting environment. After the switch to a global CDN service (Figure 4), the network degradation is not observed anymore for this same website, and the service appears to be stable from a network perspective.

Similar stable network performance was observed with other sites leveraging cloud-based CDN/security services.

Ukraine Banking Sites

In contrast to government sites, which primarily leveraged local infrastructure to serve users, nearly every major bank’s online presence in Ukraine appears to be more resilient to ongoing events. Each one uses the services of public cloud providers and, in some cases, both a public cloud as well as a specialized cloud security service, such as Imperva. As a result, with few exceptions, Ukrainian banks have experienced significantly less service volatility than government sites.

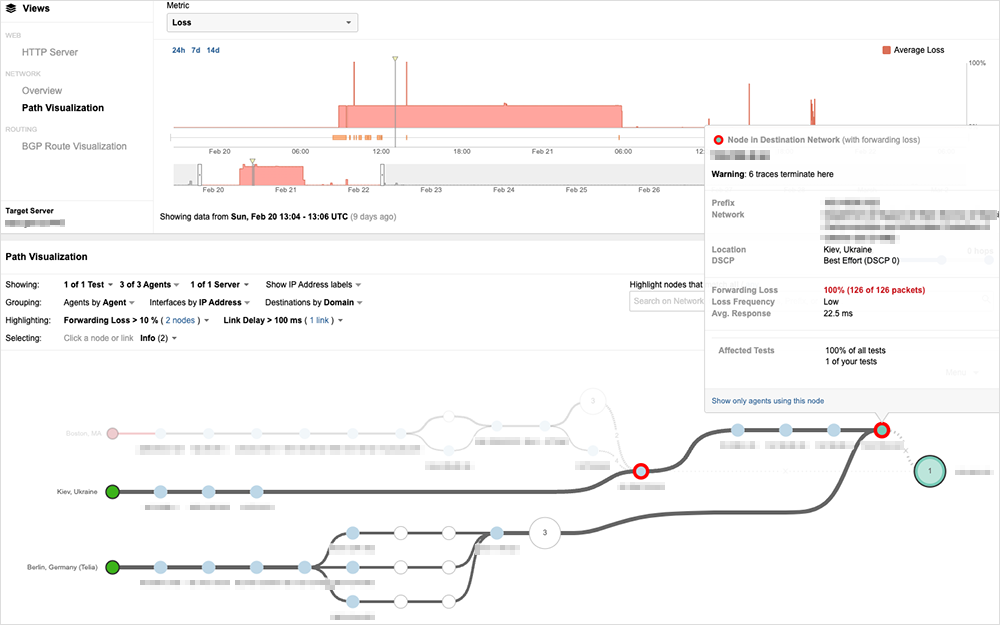

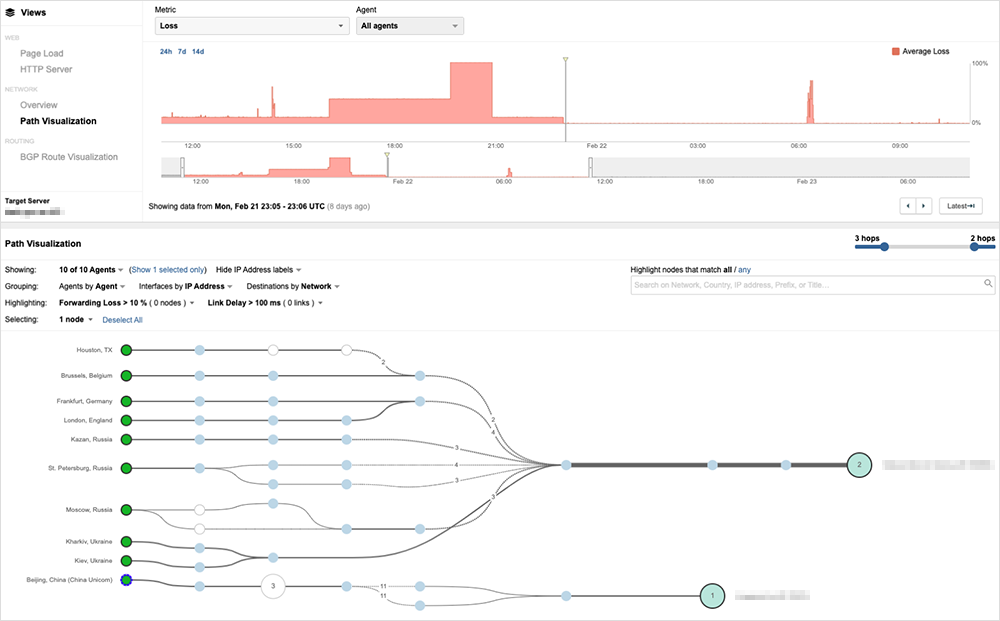

Figure 5 shows the network degradation with one major bank not already leveraging cloud services prior to recent events. Before February 21, 2022, this bank was serving traffic from a single hosting site via a single ISP, which meant traffic congestion events like a DDoS attack would be difficult to mitigate. However, on February 21st and 22nd, just before the invasion began, the bank migrated its frontend service delivery to Imperva, a service that has a distributed global presence and scalable security mechanisms necessary to fend off high-scale DDoS and application-level attacks. After fully migrating to this service, the availability of this site has been good.

In the days leading up to the Imperva switchover, we observed network behavior indicative of efforts to block traffic originating from Russia. The bank already appeared to be blocking traffic from China, but on February 21, traffic inbound from Russia began to experience prolonged and total loss in the bank's ISP provider, Infocom Ukraine. This could be reactive to an attack pattern or purely as a precaution. This kind of directed, rapid-onset loss is not likely the result of a DDoS or other targeted attack, but more likely something like intentional source-based remotely triggered blackhole (RTBH) filtering implemented by the bank via their ISP.

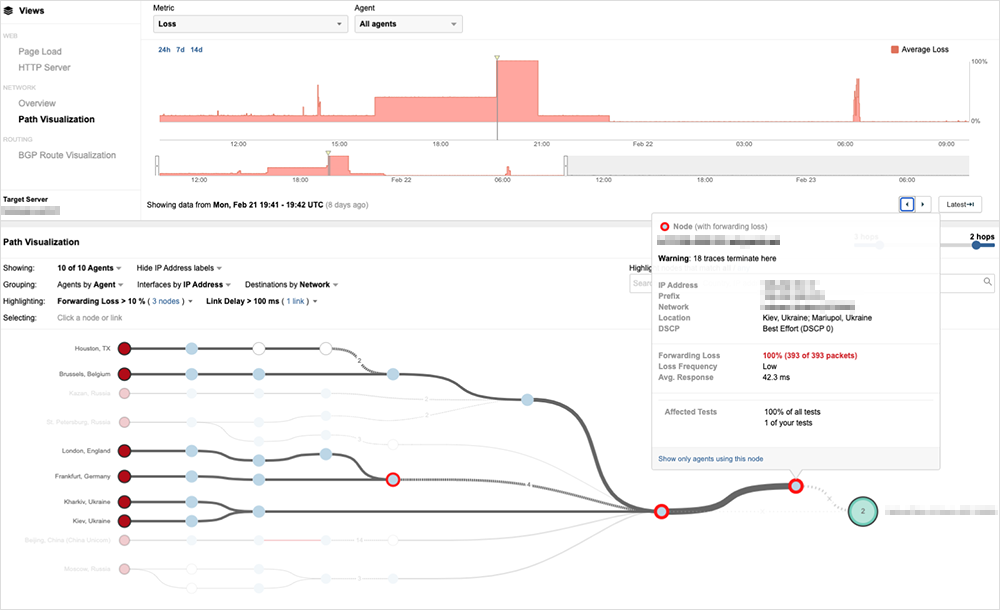

Later, on February 21 around 19:41 UTC, ThousandEyes tests show complete network loss for all traffic destined to the bank, with all loss occurring at another router in the Infocom ISP network. This may indicate a switch to a destination-based blackhole policy via the same ISP.

About an hour later, at 20:55 UTC, all traffic returns to normal, and the bank website comes back online (except for connections from China, which are blocked by default).

One explanation for this apparent filtering might be attempts to implement a network-level DDoS mitigation policy. However, neither the source nor the destination filtering was precipitated by traffic patterns that are typical of DDoS attacks previously observed, and the timing coincided with the start of the migration to Imperva, suggesting that the bank could have been taking preemptive measures to shield its systems in preparation for the impending service changes.

Three hours later, we see the first evidence of the cutover to Imperva. On February 21, around 23:00 UTC, traffic originating from China started getting routed to Incapsula network nodes (part of Imperva’s service) while traffic from other locations was being sent directly to the destination.

Finally, on February 22 around 21:51 UTC the full cutover to Imperva appears to have been completed, with all traffic routed to the Incapsula network. In addition, we can see that application traffic is now being served by Imperva (Incapsula) rather than by the Ukrainian bank itself.

Once this bank switched over to Imperva, they were able to implement what appears to be a source-based application-level blackhole policy. Instead of blackholing Russian traffic at the network level, we can see from ThousandEyes application tests that Russian traffic is now blocked at the application level, with HTTP 403-Forbidden errors.

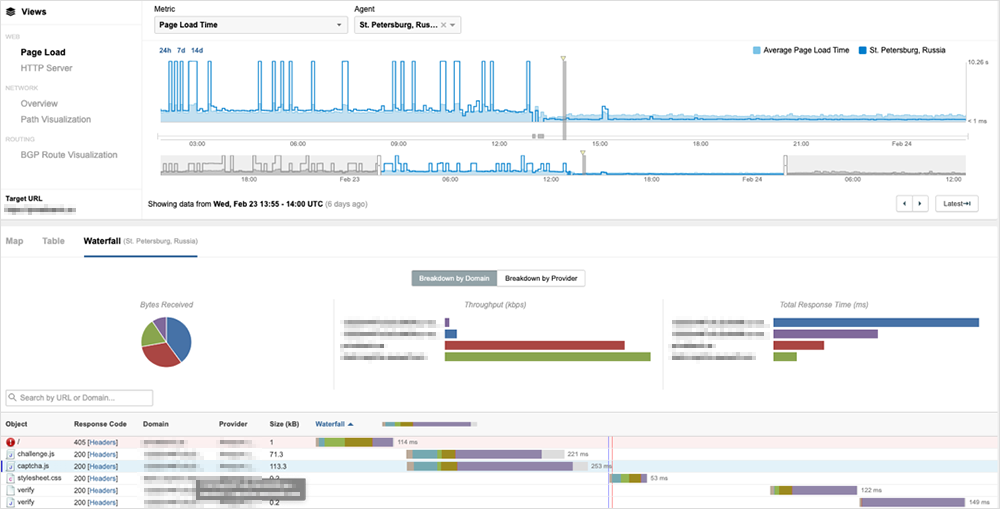

Unlike the prior example, another Ukrainian bank was already using a cloud provider (Amazon Web Services) to host its services, which allowed them to initiate application-level security policies on short notice. They also took a slightly different approach. Instead of blocking traffic originating only from Russia, this bank leveraged AWS WAF (web application firewall) services and implemented a CAPTCHA security check for any traffic originating from global locations, while allowing traffic from Ukraine locations to access their banking site unhindered.

We can see this bank put this policy in place on February 23, 13:00 UTC. ThousandEyes application tests show the website operating normally prior to February 23. Around 13:00 UTC, this website begins implementing application-level security policies. First, traffic from all global locations either times out due to servers not responding, or receives various HTTP errors from their servers, like HTTP 502 Bad Gateway. This is indicative of a cutover to new application services on AWS, which in this case is Amazon’s WAF (web application firewall) service. We can see this from the serving domain in the ThousandEyes web page components view.

By 13:55 UTC, the cutover is complete and all global locations are now served an HTTP 405 error, which is the response when a CAPTCHA page is presented. We can see the CAPTCHA page being served in the Page Load view (captcha.js). This CAPTCHA page is not present for web traffic originating from inside Ukraine.

This provides another good example of how cloud and edge security services can provide uninterrupted service for key regions while simultaneously putting effective security measures in place for regions of concern. After the cutover to AWS WAF on February 23, this Ukrainian bank has provided reliable access to its online banking site to users across Ukraine.

In conclusion, the use of cloud hosting and security providers seems to have largely helped the financial websites in Ukraine maintain high uptimes. We are continuing to monitor the situation for new developments.